What are the linkages between national savings and sustainable economic growth? Why are there differences in the amounts of savings between different countries? In March, we introduced our research on Ghana at the UNU-WIDER Domestic savings project workshop. A compilation of the different working papers presented will lead to a book on domestic savings in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The volume will help unlock the mystery of domestic savings.

The topic of savings is an important issue in economics research and has been since the beginning of the discipline. In SSA, the ability of countries to finance their developmental needs is critical. The greater the domestic savings, the greater is the much-needed flexibility to formulate and implement ‘homegrown’ policies to confront growth and development challenges.

Additionally, Africa’s large informal sector likely holds significant financial resources that unfortunately do not currently go through the formal financial system. Accounting for such informal savings would increase the level of savings in the country and create opportunities to tap into informal sources of credit. These opportunities can improve domestic savings mobilization and ultimately increase the rate of economic activity.

Cross-country differences shape savings outcomes

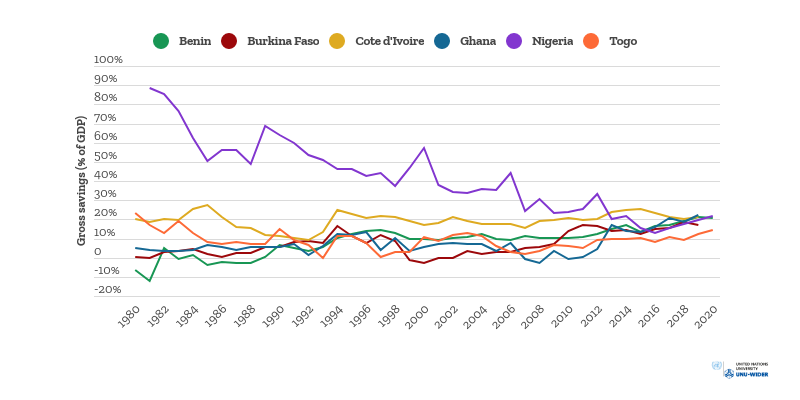

In SSA countries, both national and private savings are low, though there is some heterogeneity across countries. For instance, while Ghana is classified as a lower-middle income country, its savings do not compare favorably to West African neighbors, such as Nigeria and Cote d’Ivoire (see Figure 1). These differences may be due to a combination of socio-cultural and political economy factors. The cross-country heterogeneity we observe demonstrates how the savings behaviour of different countries is shaped.

In Ghana for example, the impounding of people’s property and assets, during military regimes and the recent banking sector clean-up, which led to a vast majority of people losing their savings, can have significant impacts on savings culture. Households and firms may view conventional bank accounts as unsafe and hold savings in less conventional places.

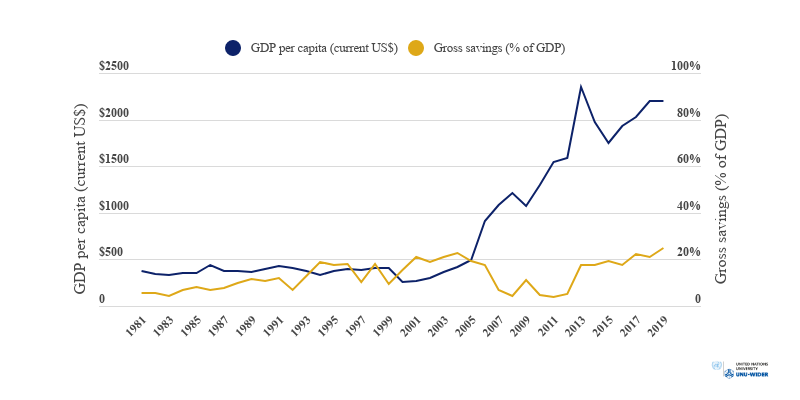

While it is generally believed that the level of saving in a country is a function of its income levels, Figure 2 paints a different picture for Ghana. Ghana bucks the general regional trend with relatively constant savings rates since 2005, despite large increases in per capita income levels. One, therefore, begins to wonder what else may be driving the saving behaviour in Ghana.

The nature of the savings-to-income relationship is an interesting one. Up until 2006, the savings rate did not diverge significantly from per capita income, although it did fluctuate some after 1990. But after 2005, during periods of increased economic growth, gross savings fell inversely. This could indicate a possible role for future expectations in aggregate savings’ behaviour, or that the direction of causality can be reversed. The inverse relationship shown in figure 2 from 2005-2017 is clearly contrary to what is generally expected.

This paradox makes the current domestic savings book project interesting. The project allows us to explore the role that political economy issues play, and to use empirical data, to observe and explain the savings behavior of households in Ghana.

What can Ghana do about domestic savings?

Our findings suggest that growth in income per capita is important in determining savings in Ghana, but that other constraints intervene to weaken the relationship. This has important implications for macroeconomic policymaking, which targets sustained economic growth and welfare improvements. Conventional tools need to be paired with prudent management of the nation’s resources and a more conducive environment for private sector economic activities.

Additionally, given the evidence for the supportive role of monetary and fiscal policies in the savings behavior of economic agents in Ghana, these need to be pursued to encourage savings and domestic savings mobilization.

We lack crucial data

Like any rigorous research, data is critical. While some of the required data for this analysis is available from World Bank databases, it was not available for some critical variables. Therefore, our studies have partly relied on proxies. Some of the variables were completely absent or had limited data for the period of interest, which meant that they had to be excluded from the analysis. The lack of such data has important implications for the findings and policy options which emanate from the study.

For example, data on population per bank branch, active mobile money accounts, and the mobile money industry’s growth were not available for the period of interest. The absence of such important data forced us to limit the scope of our analysis. This implies a need for relevant institutions, such as the Central Bank and the Ghana Statistical Services, to develop and maintain a database with this information to facilitate future research on domestic savings.

As to our experience as researchers on the UNU-WIDER team, the institute’s approach to book projects is very appealing from our point of view. There is a great deal of utility in assembling the authors in a workshop to discuss findings, challenges, and possible solutions to the common themes. Even in hybrid format, the feedback we received was detailed and constructive. The suggestions proffered by the assigned discussants and other authors provoked further thinking on dimensions that we had not initially considered. For example, we were encouraged to include variables that capture Ghana’s external debt stock, as that has important implications on private savings.

The inputs we received will help to frame our study of Ghana in the context of the larger volume on sub-Saharan African countries, to potentially change the story of low domestic savings in Ghana and beyond.

Charles Godfred Ackah is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research (ISSER), at the University of Ghana. Professor Ackah is also an External Research Fellow with the Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham, and the Kiel Centre for Globalization, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Germany. His research interests are in economic development, empirical international trade and industrial organization in developing countries.

Dr. Monica Lambon-Quayefio is a Lecturer at the Department of Economics, at the University of Ghana. Her research focuses broadly on human development issues. Specific areas of research interest include health economics, spatial econometrics, development and experimental economics.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

- Log in to post comments